Game with a bag of chocolates

The Riddler’s puzzle from October 2nd 2020

I have 10 chocolates in a bag: Two are milk chocolate, while the other eight are dark chocolate. One at a time, I randomly pull chocolates from the bag and eat them — that is, until I pick a chocolate of the other kind. When I get to the other type of chocolate, I put it back in the bag and start drawing again with the remaining chocolates. I keep going until I have eaten all 10 chocolates.

For example, if I first pull out a dark chocolate, I will eat it. (I’ll always eat the first chocolate I pull out.) If I pull out a second dark chocolate, I will eat that as well. If the third one is milk chocolate, I will not eat it (yet), and instead place it back in the bag. Then I will start again, eating the first chocolate I pull out.

What are the chances that the last chocolate I eat is milk chocolate?

Intuition

We can rephrase the problem in order to represent the same game in a bit different way. Let’s assume that rather than starting with one bag from which we pull chocolates at random we start with a random box of chocolates with pre- defined order from which we pull chocolates one by one. The game continues as it is until we encounter a chocolate of a different type then the one which we pulled first. Then, for example, we can give the last pulled chocolote and the box with the remaining chocolates to another person and ask that person to open the box and without rearranging chocolates in it insert chocoloate which is not in the box into the random position inside the box and give back to us the box with all of the chocolates in it. After that we repeat the process.

Although this new game sounds quite different in fact the game is exactly the same. It’s quite easy to show that this is true. Let’s say we pulled \(k\) black chocolates and one milk chocolate. This information tells us what number of black and milk chocolates remains in the box, but it tells us absolutly nothing about the order of these chocolates since each order is equaly likely. Next, the other person puts the milk chocolate into the random position in the box and this doesn’t give away any information about the order of the chocolates within the box meaning that each order is equaly likely just like the random sampling process with the bag of chocolates.

Another way to rephrase the problem is by imagining that insted of inserting the chocolate back into the box we just record the number of black and milk chocolates remaining and find a new box with random arrangement of chocolates which has desired number of chocolates per each type. Again, in each case we end up with the random sequence of chocolates.

Now let’s focus on each possible arrangement of the chocolates within the box. There are two types of cases which are interesting to us, namely boxes with ordered and unordered sequence of chocolates in them. Ordered boxes will have all milk chocolates before all the black chocolates and the other way around. For any non zero number of black and milk chocolates there are always two boxes with ordered chocolates in them. One box will have all milk chocolates before the black chocolates and the other one will have them in the reverse order. In the first box, where all milk chocolates are at the beggining will be eaten until the black chocolate gets picked up in which case the black chocolate will be inserted back into the box and since all of the chocolates are black their we will always end up having black chocolate as the last one. In the second case, we will encouter the opposite arrangement where we always end up with milk chocolate at the end. In fact, ordered boxes are the only types of boxes with determenistic outcome that could be predicted exactly from the by the initial order of chocolates in the box (expect maybe some degenerate cases where there are no black or milk chocolates).

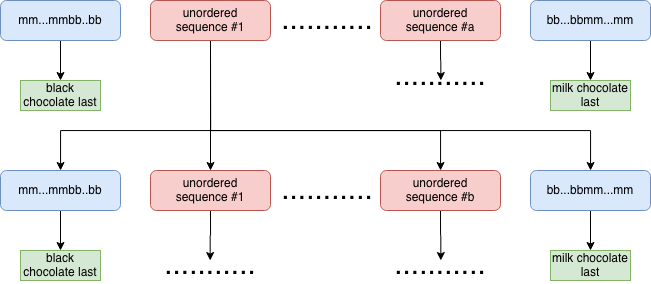

Let’s consider some general case. We start with \(m\) milk chocolates and \(b\) black chocolates. At the beggining, there are \({m + b}\choose{m}\) boxes with unique arrangements of chocolates in them. Two of those boxes have ordered sequence of chocolates in them. In one of these boxes we will always get milk chocolate at the end and in the other one will always get the black one. If we pick box with unordered chocolates then we will end up eating, for example, \(i\) black chocolates (same works for milk chocolates by symmetry). After that, we will have to pick one of the \({m + b - i}\choose{m}\) boxes. The new box will have \(m\) milk chocolates and \(b - j\) black chocolates. And for the new box we can follow the same process. We will again have two boxes with ordered chocolates and for the other boxes process repeats itself again.

In fact, we can expand solution tree and notice something special about out, in each pass of the tree we always end up in the node with black or milk chocolate meaning that parent of this note has ordered sequence.

The tree representation above shows that it doesn’t metter in which node of the tree with unordered sequence of chocolates we end up in we will always have equal probability of getting black or milk chocolate at the end of the game. This is quite surprising since it doesn’t metter what’s the initial number of black and milk chocolates we will always have equal probability of getting one of the chocolate types at the end of the game.

Prove

It’s quite easy to prove by induciton that intuition is always correct when there is at least one black and one milk chocolates. We can start by showing that for any cases where we have \(b=n\) black chocolates and \(m=1\) milk chocolate we will always get milk chocolate \(M\) as the last chocolate with probability \(0.5\).

- for \(b=1\) and \(m=1\), \(p(M \mid b=1, m=1)=0.5\) by symmetry

- for \(b=n\) and \(m=1\), \(p(M \mid b=n, m=1)=0.5\)

-

for \(b=n+1\) and \(m=1\)

There are \({n+2 \choose 1} = n+2\) unique arrangement for the chocolates. Two of these arrangements are ordered and only one of these ordered arrangements will end up with the milk chocolate at the end. The other arrangements are unordered meaning that we will end up with sequences that have \(b=n + 1-j\) and \(m=1\), for some \(j \ge 1\). We know that there are \(\frac{n}{n+2}\) unordered sequences and by induction we assume that

\(p(M \mid b=n+1-j, m=1)=0.5 \ \forall \ 1 \le j \le n \)

combining all information we get that

\(p(M \mid b=n+1, m=1)=\frac{1}{n+2} + \frac{1}{2} \frac{n}{n+2} = 0.5\)

Now, knowing that \(p(M \mid b=n, m=1)=0.5 \ \forall n \ge 1 \) we can prove by induction that the same holds for \(m \ge 2\). The previous prove was a first induction step for the general case prove since we showed that this is true for \(m=1\). The next steps will take advantage of the fact that in unordered sequences number of black or milk chocolates always gets reduced so prove could be done recursively as well.

Simulation

It’s quite easy to write a simple simulation which plays the game large number of times and produces number that’s very close to the theoretical probability. The code that I used could be found on github