IMO 2019 and solutions to the non-geometric problems

My solutions for the non-geometric IMO 2019 problems. I’m an amature in mathematics which means that these solutions might contain mistakes. Use them at your own risk

Problem 1

Solution

\[f(2a) + 2f(b) = f(f(a+b))\]Important observation: The order of the variables \(a\) and \(b\) matters in the left equation, but not in the right one. On the right side we can see that addition is commutative which implies that swapping variables in the left side shouldn’t make a difference

\[f(2a) + 2f(b) = f(f(a+b)) = f(f(b+a)) = f(2b) + 2f(a)\]Next we can explore a few corner cases

when a = 0

\[f(0) + 2f(b) = f(f(b)) \\ f(2b) + 2f(0) = f(f(b))\]we can multiply first equation by 2 and subtract second equation from it

\[4f(b) - f(2b) = f(f(b))\]therefore

\[4f(b) - f(2b) = f(2b) + 2f(0) \\ 2f(b) - f(2b) = f(0) \\ f(2b) = 2f(b) - f(0)\]and finally

\[f(2b) + 2f(a) = 2f(b) - f(0) + 2f(a) = f(f(a+b))\]when c = a + 1 and d = b - 1

\[2f(a + 1) + 2f(b - 1) - f(0) = f(f(a+b)) = 2f(a) + 2f(b) - f(0) \\ f(a+1) - f(a) = f(b) - f(b - 1)\]\(a\) and \(b\) are independent from each other and we can set them equal to any integer. Based on this fact the derived equation implies that the difference between function outputs evaluated on two subsequent integers is constant (derivative of the \(f\) function with respect to the input is constant). This means that \(\,f\) is a linear function

\[f(a) = ka + c\]for some k and c

Let’s plug this linear function into two different equations that we’ve derived before

First, for cases when b = 0

\[2f(a) + f(0) = f(f(a)) \\ 2\,k\,a + 3c = k^2a + kc + c \\ 2ka + 2c = k^2a + kc \\ 4ka + 4c = 2k^2a + 2kc\]Second, for cases a = b

\[2f(a) + 2f(a) - f(0) = f(f(2a)) \\ 4ka + 3c = 2k^2a + kc + c \\ 4ka + 2c = 2k^2a+kc\]We can subtract the second equation from the first one and we will get that \(2c = kc\) which means that \(k = 2\) or \(c=0\). But from the first equation we can see that even if \(c=0\)

\[4ka + 4c = 2k^2a + 2kc \\ 4ka = 2k^2a \\ k = 2\]We can plug linear function with a fixed k into the general formula

\[f(2a) + 2f(b) = f(f(a+b)) \\ 4a + c + 4b + 2c = f(2a + 2b + c) \\ 4a + 4b + 3c = 4a + 4b + 3c\]This equality implies that relation will hold for any possible \(c\), but because we know that function \(f\) always outputs integers, it means that \(c\) has to be an integer.

Final equation

\[f(a) = 2a + c\]where \(c \in \mathbb{Z}\)

Problem 3

Solution

It’s obvious that the only way the game cannot be finished is when a fully connected graph or a sub-graph with 3 or more nodes has been created. In this context, a subgraph is a subset of nodes which is completely disconnected from all other nodes, but all nodes within this set are connected to each other. It’s impossible to finish the game because we need to have “missing” edges in the graph in order to make a move.

Another important observation is that with each step we reduce the total number of links in the graph by 2. For example, let’s focus on 3 nodes, namely A, B and C. Let’s say A-B and A-C are connected, but B and C are not connected (just like in the example above). We can say that A has 2 friends, B has 1 friend and C also has 1 friend. After 1 operation we get A with no connections, which means that this person has 0 friends, but B and C have 1 friend each (exactly as it was before). Of course, B and C got different friends, but the number of friends remained the same. We can think that during each step we reduce the number of edges by 2 in one and only one node. It means that when a node has an odd number of friends we will never be able to get 0 edges for this node. Nodes with an odd number of edges will have at least 1 edge at the end of the game. But it’s not a problem for nodes that have an even number of nodes. For them, a node could be isolated from all other nodes which means that it will have 0 edges.

At least in principle, we should be able to get to a group of users with 0 or 1 connection, but we cannot just subtract 2 edges from some random node per each event, since the node might not have any legal moves that would allow us to get rid of the two edges. Simple example is a fully connected graph that has 3 nodes where each node is connected to each other.

Initially, we don’t have any fully connected subgraphs in the graph. It’s easy to see, since the only 2 possible fully connected subgraphs should contain either 1010 nodes with 1009 edges each or 1011 nodes with 1010 connections each. Second case is impossible, since we have only 1009 nodes with 1010 edges. The first option could have been possible, but the problem is that we have 1009 nodes with 1010 edges in addition to 1010 nodes with 1009 edges which means that we cannot have fully connected subgraphs with 1010 nodes and 1009 edges. It’s easy to see. Let’s take 1 node that has 1010 edges. This node can be connected to all other 1008 nodes with 1010 edges, but we will need to connect it to 2 more nodes in order to get 1010 edges. This means that this node has to be connected to at least 2 nodes that have 1009 connections. And this implies that each node with 1009 edges should be connected to at least 1 node with 1010 friends and it means that we cannot have a fully connected subgraph in the graph.

Since we don’t have any fully connected subgraphs, the only reason why we might not reach a desirable goal is in case at least one fully connected subgraph will be formed. We can show that any possible formation of a fully connected subgraph could be prevented.

Let’s say that we keep changing the graph by applying events to the random nodes in the graph, we repeat this process until we reach the state of the graph that’s one step from forming the fully connected subgraph. Let’s say that we can put all of the nodes that will be formed into a fully connected subgraph in the next step, into one group. With this configuration, there are two distinct ways in which fully connected subgraphs can be formed. Either in the next step node in the group will lose 2 connections after which fully connected subgraph will be formed or there is another node outside of the group which is connected to exactly 2 nodes from the group and will lose 2 connections in the next step.

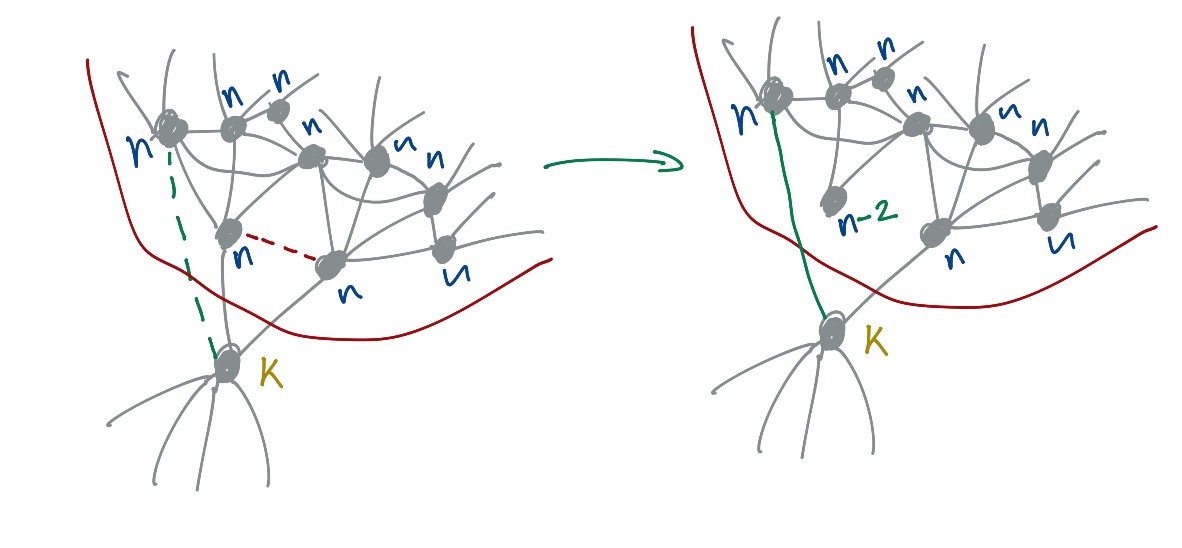

Let’s consider the first case.

In the image above, we can see that if we remove 2 edges from the node that has \(k\) edges then a fully connected subgraph will be formed (the red dashed line shows a new link that could be formed in the next step). But we can also see that it’s not the only step that we can perform. There are a few other steps that we can do and one of them has been shown in the image above (with the green dashed line). We can see that after this step one of the nodes lost 2 connections and we no longer can create a fully connected subgraph from the nodes in a single step. Basically, we can see that formation of the fully connected graph can be prevented in this case.

Notice that to prevent formation of a fully connected subgraph, we had to use 4 nodes, which means that \(n \ge 3\) (plus one node outside of the group). But we will still have a problem for case, for example, when \(n=k=2\), because in this case a fully connected subgraph will be formed and there will be no way of reducing the number of edges in each one of these nodes. This case will be considered separately, since it reveals a bigger problem with subgraphs that contain only nodes that have an even number of edges. This special case will be discussed at the very end.

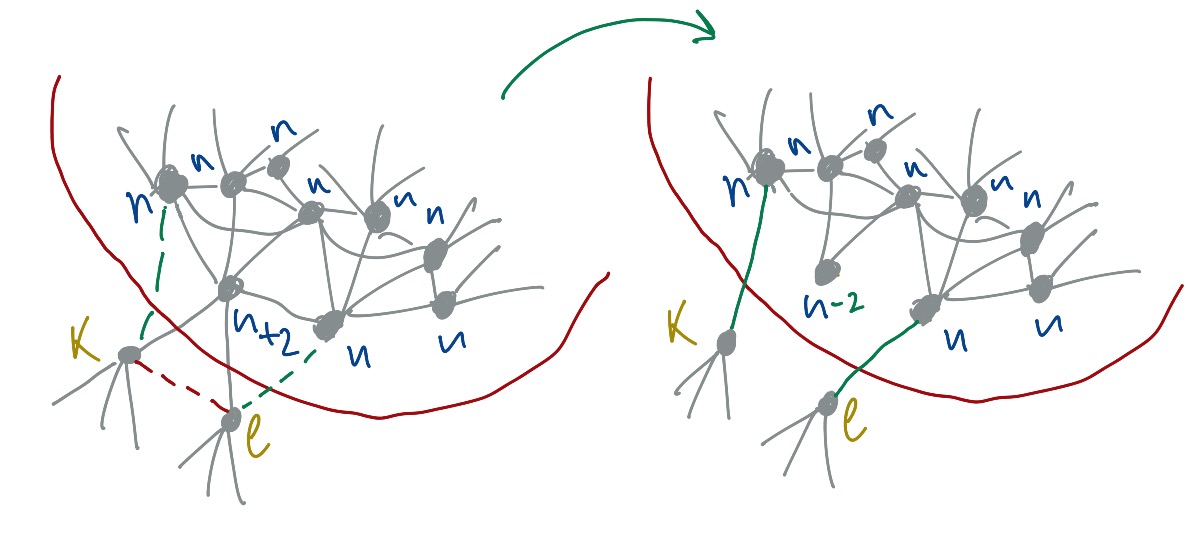

Let’s consider second case

And again, we need only 3 nodes from the group in order to be able to perform this operation. As before, we can either fail to finish the game by creating an edge between two nodes with \(k\) and \(l\) nodes respectively (the red dashed line), in which case a fully connected subgraph will be formed and we won’t be able to finish the game. But as before we can prevent this from happening by doing another move (shown with two green dashed lines). After two steps we no longer can create a fully connected subgraph in one step which means that problem has been postponed again. And as before, we still can have problems with this approach, for example, for case when \(n=k=l=2\).

And finally, we need to make sure that we can prevent formation of a fully connected subgraph in first and second cases when \(n=k=2\) and \(n=k=l=2\) respectively. Let’s explore the first case. We have 4 nodes and each node has 2 edges. In the next step ,we will get 3 nodes with 2 connections each which will be a fully connected graph. In fact, a subgraph in which all of the nodes have an even number of edges will inevitably form a fully connected subgraph with at least 3 nodes.

We can show that every graph (or subgraph) with all of the nodes that have an even number of connections will eventually produce at least one fully connected subgraph in which each node has 2 or more edges (even number of edges). First, notice that in each step some node in the graph loses 2 edges. Because we cannot get nodes with an odd number of edges we will have to end up with a graph that has no edges at all. This goal is clearly impossible. Let’s imagine that this is possible. Imagine that we are one step before a graph with no edges has been formed. Since we remove 2 edges each step it implies that there should be a single node with two edges. This is impossible, because if one node is connected to some other node then there must be another node with more than one edge which is a contradiction. This proves that subgraphs with nodes that have even number of edges are as problematic as fully connected subgraphs.

We can avoid formation of the graphs that have only nodes with even number of edges in exactly the same way that we did it for the graphs that we’ve considered before. Basically, we need to consider cases after which we will get in the next step a decoupled subgraph with all of nodes that have only an even number of edges and prevent it from happening in exactly the same way as in the previously considered cases. As it has been shown before, origianl graph doesn’t have subgraphs with only nodes that have an even number of edges, because the original graph has only one subgraph and by initial definition we mixture of nodes with odd and even connections.

By following all of these steps we will guarantee that fully connected subgraphs will not be formed and therefor desirable goal could be reached.

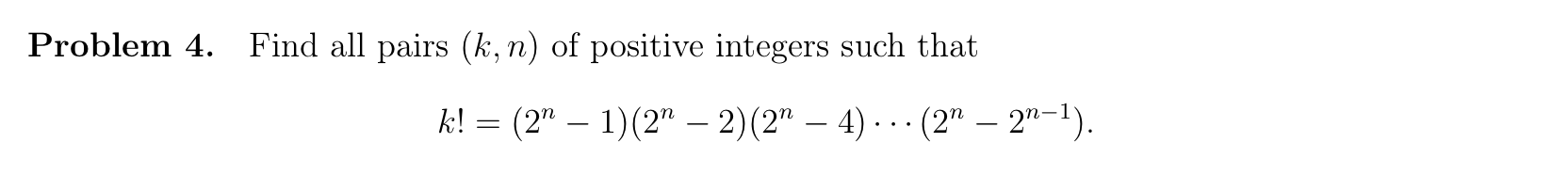

Problem 4

Discovering simples solutions manually

It’s easy to find a few simple solutions for small \(n\). For \(n=1\), \(k=1\) and for \(n=2\), \(k = 3\). It’s interesting to note that for \(n=4\) we get \(\frac{8!}{2}\) which is not a solution, but nevertheless it’s pretty close.

Rewriting expression with exponents

we can express every multiplier on the right hand side \((2^n - 2^k)\) with \(2^k(2^{n-k} - 1)\) and we will get \((2^n - 1)(2^n - 2)(2^n - 4)...(2^n - 2^{n-1}) = 2^{\frac{n(n-1)}{2}}\prod^{n}_{m=1} (2^m - 1)\)

Note that we separated odd from even numbers and in order to understand what kind of \(k\)s are possible we need to study odd numbers

Studying behaviour of the odd numbers

for \(f(n) = 2^n - 1\) and first few \(n\) values we get the following table

| n | f(n) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 3 |

| 3 | 7 |

| 4 | 15=3*5 |

| 5 | 31 |

| 6 | 63=337 |

| 7 | 127 |

| 8 | 255=3517 |

| 9 | 511=7*73 |

| 10 | 1023=11331 |

From the table above we can make a few interesting observations

- for \(n=5\) we get 31, which is a prime number. It means that for \(n \ge 5\), \(k\ge31\)

- \((2^n-1) \mod 7 = 0\) when \(n\) is divisible by 3

- \((2^n-1) \mod 5 = 0\) when \(n\) is divisible by 4

from 2nd and 3rd observations we can see that in the product \(\prod^{n}_{m=1} (2^m - 1)\) we get more 5s than 7s which is quite unusual behaviour for the \(k!\) function, since there we expect more 5s than 7s

it’s easy to show that for any \(n\ge9\) we will always have more 7s than 5s, which is a problem for \(k!\), since there we expect more 5s than 7s when we factorize \(k!\) into primes. This statement implies that we will never get any solutions for \(n\ge9\)

And finally, from the first observation we can see that for \(n\ge5\), \(k\ge31\). We’ve already tested solutions for \(1\le n \le 4\) and found 2 solutions, but for \(k\ge31\) we need to have way more factors that we really get from the \(2^n-1\) numbers multiplied together. For example, there is no prime number 29 in factorization from every \(2^n-1\) that we’ve calculated, which means that we don’t have solutions from \(n\lt9\) and therefore we don’t have more solutions apart those that has been already discovered

All possible solutions

- \(n=1\) and \(k=1\)

- \(n=2\) and \(k=3\)

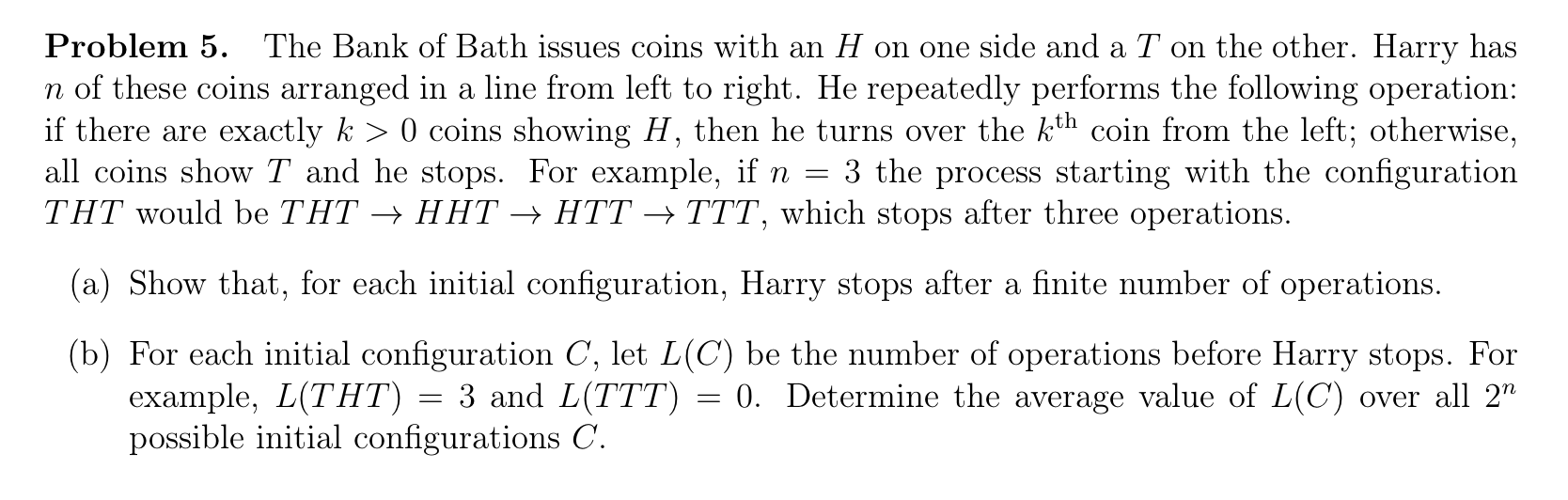

Problem 5

Solution to this problem can be found in a separate article: Coin flipping game from IMO 2019